Introduction

Why do some memories stick for years while others vanish in minutes? How can we reliably improve our ability to remember names, numbers, and facts? This guide explains how the brain stores information, how memory systems work, and the most effective, research-backed methods to increase your capacity to remember—with practical exercises you can start today. We’ll also clarify whether memory training requires special talents (spoiler: it doesn’t) and why recalling names often feels different from recalling numbers.

How Memory Works: The Big Picture

Memory is not a single “thing” in one place. It’s a set of processes and systems distributed across brain networks.

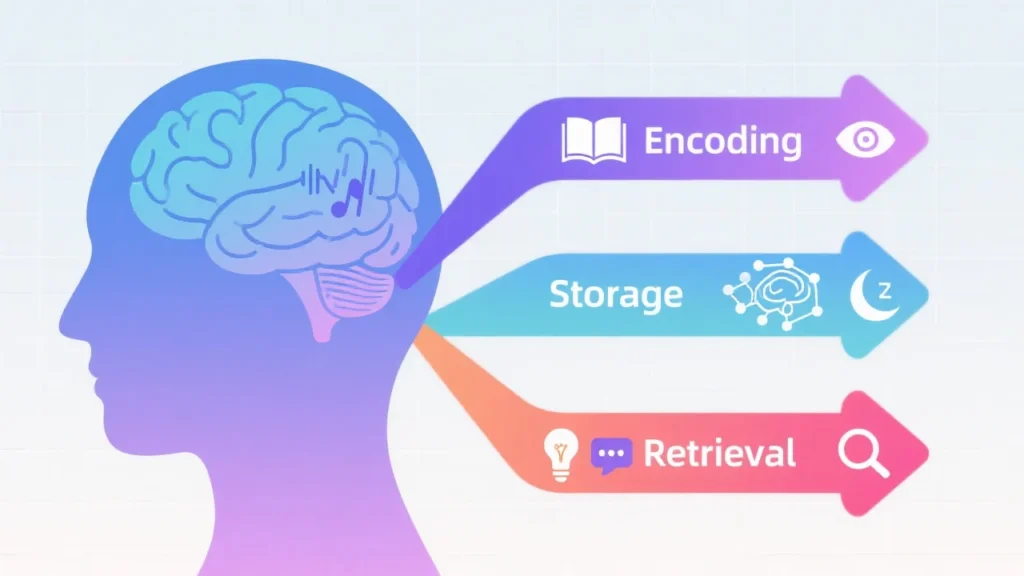

The Three Main Stages of Memory

- Encoding: Transforming incoming information into a neural representation. Attention and meaning are critical here.

- Storage/Consolidation: Stabilizing memories over time, especially during sleep. The hippocampus acts as a rapid “indexer,” linking elements of an experience; neocortex gradually stores long-term knowledge.

- Retrieval: Re-accessing stored information using cues. Context and mood can help or hinder retrieval.

The Major Memory Systems

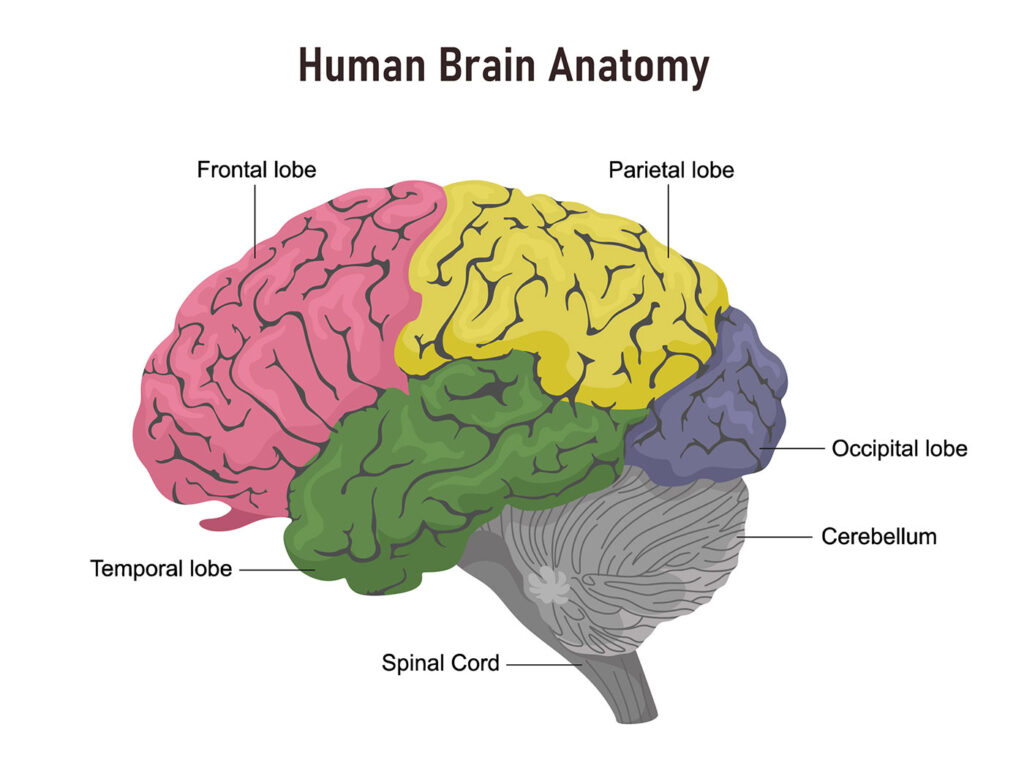

- Working Memory: Short-term mental workspace (holding a phone number in mind). Linked to prefrontal and parietal networks.

- Episodic Memory: Memory for personal experiences (what happened yesterday). Hippocampus-dependent.

- Semantic Memory: General knowledge and facts (capitals, word meanings). More neocortical over time.

- Procedural Memory: Skills and habits (cycling, typing). Basal ganglia and cerebellum are key.

“Neurons that fire together wire together.” With repeated activation, synapses strengthen (long-term potentiation), creating more efficient networks for the learned material.

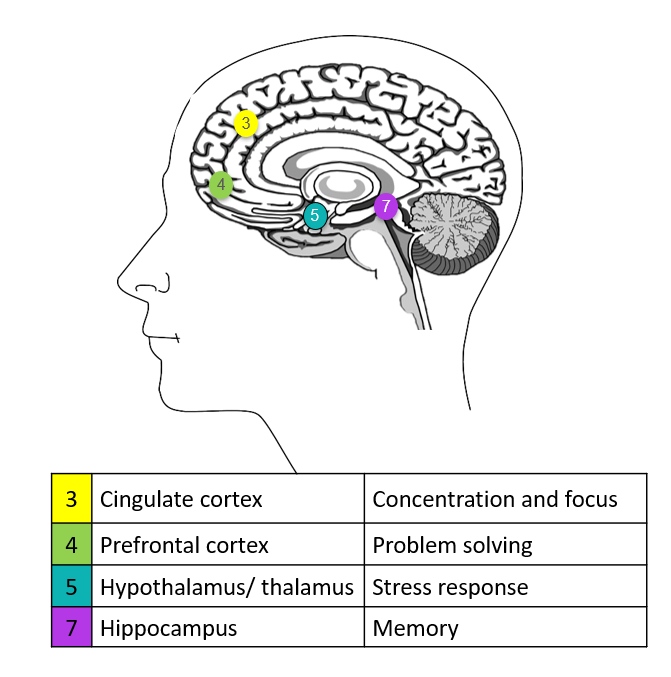

Reference media to understand the brain anatomy

How the Brain Stores Information: From Bits to Networks

- Neural Coding: Information is represented by patterns of activity across populations of neurons, not a single “memory cell.”

- Associations: The hippocampus binds together “who-what-where-when” into an event. Stronger associations and richer contexts create more retrieval paths.

- Consolidation: Over hours to days (and during sleep), memories become less hippocampus-dependent and more distributed in the cortex.

- Reconsolidation: Every time you recall a memory, it becomes malleable and can be updated, strengthened, or distorted.

“Memory is the residue of thought.” — Daniel Willingham.

The more deeply you think about something (meaningful connections), the more likely you are to remember it.

Can Anyone Train Their Memory—or Does It Need Special Talents?

Most people can significantly improve memory performance with the right techniques and consistent practice. World memory champions almost universally rely on learnable strategies (mnemonics, visualization, spaced practice), not innate photographic memory. While individual differences exist (e.g., working memory capacity), technique, structure, and practice are the biggest levers.

Quote: “Geniuses are made, not born. And they are made by training and practice.” — Laszlo Polgar

Proven, Reliable Methods to Increase Memory—With Practical Examples

1) Spaced Repetition (Beat Forgetting With Timing)

- What it is: Reviewing information at increasing intervals to counter the forgetting curve.

- Why it works: Reinforces synaptic connections right when they’re weakening, improving long-term retention.

- How to do it:

- Day 0: Learn; Day 1: quick review; Day 3; Day 7; Day 14; Day 30.

- Use apps like Anki or set calendar reminders.

- Example: To memorize 50 medical terms, create flashcards with the term on one side and a concrete definition plus an image on the other. Review the schedule above.

2) Active Recall (Test Yourself, Don’t Just Reread)

- What it is: Deliberately retrieving information from memory without looking at the answer first.

- Why it works: Retrieval itself strengthens memory traces.

- How to do it:

- Cover the answer and explain it aloud from memory.

- Use practice questions or teach it to a friend.

- Example: After reading a chapter, close the book and write a 5-point summary from memory. Check what you missed and re-encode.

3) Elaborative Encoding (Make It Meaningful)

- What it is: Connecting new information to existing knowledge with examples, analogies, and “why/how” questions.

- Why it works: Richer networks create more retrieval cues.

- How to do it:

- Ask: How does this relate to what I already know? Why is it true?

- Example: Learning “mitochondria = energy production”? Connect it to an analogy: “Mitochondria are the city’s power plants; glucose is the fuel; ATP is electricity.”

4) Dual Coding (Words + Images)

- What it is: Combine verbal and visual representations.

- Why it works: Two independent pathways boost recall.

- How to do it:

- Draw diagrams, timelines, and concept maps; pair terms with simple sketches.

- Example: When studying history, create a labeled timeline and a quick map of locations.

5) Chunking (Group to Expand Capacity)

- What it is: Organizing many units into meaningful clusters.

- Why it works: Working memory can handle about 4 “chunks,” not unlimited items.

- How to do it:

- Group numbers by pattern (e.g., dates, area codes).

- Example: Remember 149217761989 as 1492–1776–1989 (Columbus, US Independence, Fall of the Berlin Wall).

6) Method of Loci (Memory Palace)

- What it is: Place vivid mental images of items along a familiar spatial route (home, commute).

- Why it works: Spatial memory is ancient and powerful; images + locations create strong cues.

- How to do it:

- Choose a route, select 10–20 loci, and “place” each item as a bizarre, vivid scene at each spot.

- Example: Grocery list: “eggs” exploding on your doormat; “spinach” as vines wrapping your staircase; “rice” pouring from your lamp.

7) Interleaving (Mix, Don’t Block)

- What it is: Alternate topics or problem types during practice.

- Why it works: Builds discrimination and flexible retrieval.

- How to do it:

- Study A-B-C-A-B-C, not A-A-A, then B-B-B.

- Example: In math, mix algebra, geometry, and stats problems within a session.

8) Sleep, Exercise, and Stress Management (Biology Matters)

- Sleep: 7–9 hours; slow-wave sleep aids declarative memory; REM supports integration and creativity.

- Exercise: Aerobic activity elevates BDNF and improves neuroplasticity.

- Stress: Chronic stress impairs hippocampal function; short, manageable stress can sometimes enhance focus.

- Example routine: 30 minutes brisk walking 5x/week; consistent sleep schedule; 5-minute breathing drills before study.

9) Retrieval Cues and Context Control

- What it is: Create and use cues linked to the encoding context.

- How it works: Matching internal state and environment aids recall.

- How to do it:

- Use the same pen or music during study and practice tests; create keyword cue lists.

- Example: Before an exam, rehearse a 10-keyword cue sheet that unlocks entire topics.

10) Teach-Back and Feynman Technique

- What it is: Explain the concept simply as if to a child.

- Why it works: Exposes gaps and deepens understanding.

- How to do it:

- Write a plain-language explanation and refine until it’s clear and concise.

Want to turn these techniques into a simple daily routine on your phone? Check out our companion guide: “Boost Your Brain: Top Mobile Apps for Memory & Learning” — a practical tour of spaced-repetition flashcards, smart reminders, and name/number trainers you can start using today.

Are Names Different from Numbers? Why Some Things Are Harder to Remember

Yes—names and numbers typically engage memory differently.

- Names (Proper Nouns):

- Often low in inherent meaning and arbitrary (“Widad,” “Alex”), offering few hooks.

- Heavily dependent on associative and face-name binding in the hippocampus and temporal lobes.

- Common failure: “tip-of-the-tongue” for names is frequent because there are fewer semantic routes to them.

- Numbers:

- Naturally chunkable (dates, prices, patterns).

- Can tie into existing semantic frameworks (math facts, familiar sequences).

- Easier to apply chunking and rhythm (e.g., 3–3–4 phone patterns).

Practical fixes:

- For names: Attach a distinctive image + rhyme or alliteration + a feature.

- “Nadia” → imagine “nadir” (lowest point) turned upside down on her glasses; “Nadia with navy glasses.”

- Repeat back: “Nice to meet you, Nadia.” Use the name 2–3 times naturally in the first minute.

- For numbers: Chunk into meaningful units; create a mini-story connecting chunks; attach to dates you know.

Practical, One-Week Memory Training Plan

- Daily (20–30 minutes):

- Day 1: Learn 20 items with Method of Loci; review via spaced repetition (D1, D3, D7).

- Day 2: Build 10 flashcards for key facts; practice active recall; add images (dual coding).

- Day 3: Name drill: meet or imagine 10 faces (photos), create an image + feature + repetition for each.

- Day 4: Numbers drill: memorize two 10-digit strings using chunking + story.

- Day 5: Interleave: mix names, numbers, and facts in one session.

- Day 6: Teach-back: record a 3-minute explanation of a topic without notes.

- Day 7: Cumulative retrieval test; sleep 8 hours.

Support habits:

- 7.5–8.5 hours sleep, 30 minutes moderate exercise, short mindfulness session, and a distraction-free study block (phone on airplane mode).

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Passive rereading: Replace with active recall.

- “Cramming only”: Use spaced repetition for durable memory.

- No imagery: Add vivid, unusual images to anchor recall.

- Overload: Use chunking and limit sessions to focused blocks (25–45 minutes).

- Inconsistent sleep: Protect it—it’s part of studying, not optional.

We Ask, and Experts Answer

Q1: Do I need a “photographic memory” to benefit?

No. Photographic memory is largely a myth. Champions train with mnemonics, spacing, and visualization. You can too.

Q2: How long until I notice improvement?

Many people see gains in 1–2 weeks of consistent practice (20–30 minutes/day), with substantial improvements over 1–3 months.

Q3: Will memory techniques help with complex subjects, not just lists?

Yes. Use elaboration, dual coding, and teach-back for concepts; use spaced retrieval for definitions and frameworks.

Q4: Are supplements necessary?

For healthy individuals, lifestyle (sleep, exercise, stress, diet) and methods described here are the primary drivers. Consult a clinician before taking any supplement.

Q5: What if I’m older—can I still improve?

Absolutely. Neuroplasticity persists across the lifespan. Techniques may require more repetition, but the benefits are real and significant.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

- Memory is a set of brain processes—encoding, consolidation, and retrieval—distributed across networks.

- Anyone can train their memory. Technique and consistency beat raw talent.

- Use the “big four”: spaced repetition, active recall, elaboration, and dual coding. Support with sleep, exercise, and stress management.

- Names are often harder because they’re less meaningful; use face-feature imagery and immediate repetition. Numbers lend themselves to chunking and patterns.

- Start small, be consistent, and track progress. Your memory will grow with the right practice.