Fasting is having a moment—people do it for weight goals, metabolic health, religious practice, simplicity, or just because breakfast feels optional.

“Okay… but where’s the line between a normal fast and something dangerous?”

Let’s make it clear, practical, and safety-first—because fasting and starvation aren’t the same thing, even though some body processes overlap.

Quick disclaimer (worth saying upfront)

This article is general education, not medical advice. If someone is pregnant, underweight, has a history of eating disorders, takes glucose-lowering medication, or has a chronic illness, fasting should be discussed with a clinician.

What “fasting” usually means (in real life)

In most modern contexts, intermittent fasting means you choose a time window to eat and a time window not to eat, while still meeting overall nutrition and hydration across the week.

Common examples:

- 12:12 (12 hours fasting, 12 hours eating) – often just “don’t snack late”

- 14:10 – a gentle step up

- 16:8 – popular schedule

- OMAD (one meal a day) – more intense, not for everyone

For many people, the “fast” period still includes:

- Water

- Unsweetened tea/coffee

- Sometimes electrolytes (depending on approach)

What “starvation” means (and why it’s different)

Starvation is prolonged inadequate intake where the body is forced to sacrifice tissue and systems to survive—often unintentionally, often with compounding risks (stress, illness, dehydration, micronutrient deficiency).

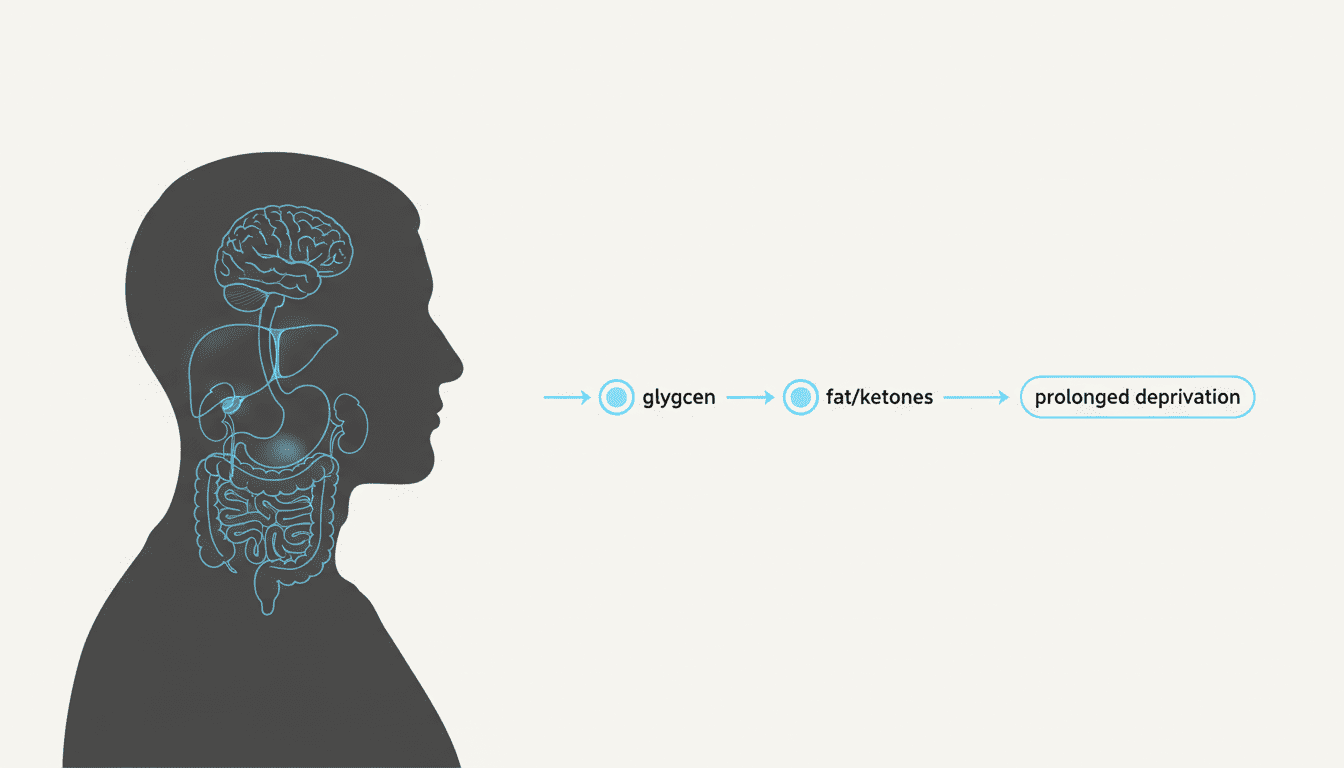

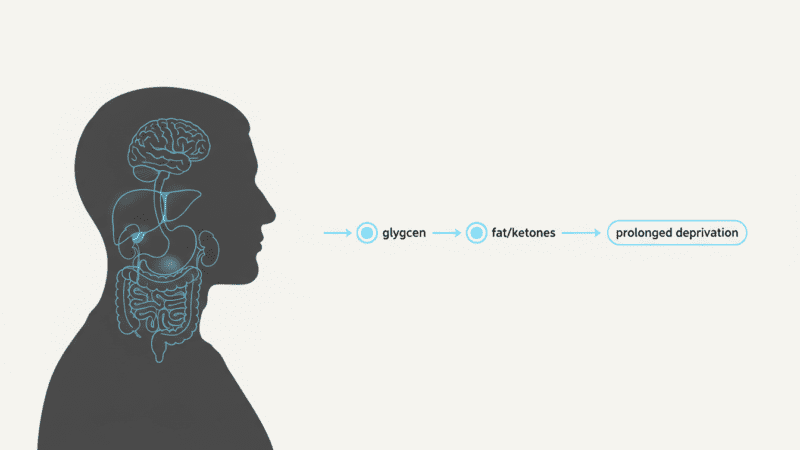

Your hub article explains the general progression: glycogen use → glucose-making from other materials → increased fat use/ketones → prolonged deprivation and organ stress.

Read it here: What Happens to the Human Body Without Food: A Day-by-Day Breakdown

The key difference isn’t just “hours without food.” It’s the context:

- Are you hydrated?

- Are you nourished overall?

- Are you doing this with a plan—or because you can’t access food?

- Are you medically vulnerable?

Fasting vs starvation: a simple comparison table

| Topic | Intermittent fasting (typical) | Starvation (risk state) |

|---|---|---|

| Intent | Chosen, planned | Often unchosen or out of control |

| Duration | Usually hours; sometimes 24 hours | Days to weeks |

| Hydration | Usually maintained | Often compromised |

| Nutrition overall | Often adequate weekly intake | Deficient calories + micronutrients |

| Body response | Uses stored energy; may produce ketones | Increasing breakdown of fat + muscle; escalating risk |

| Supervision | Sometimes guided | Often none; often emergency context |

| Biggest danger | Overdoing it, poor refeed, dizziness, binge-restrict cycle | Electrolyte imbalance, infection risk, organ strain |

What actually happens in your body during a “normal” fast

Even short fasts can feel dramatic because hormones and fuel use shift.

1) Early phase: using stored carbohydrate (glycogen)

At first, your body leans on glucose and glycogen. That’s why people often feel:

- Hunger waves

- Irritability

- “Food thoughts”

- Lower workout intensity

This mirrors your hub article’s Day 1: Glycogen phase framing.

2) Mid phase: more fat use + ketones (for some people)

As the fast continues, the body increases fat breakdown and may increase ketone production. This is where some people report:

- Clearer appetite control

- Steadier energy

- Or the opposite: headaches and fatigue (often hydration/electrolyte related)

“Ketosis is a survival mechanism. It allows the brain to function when glucose is scarce…”

Dr. Lisa Mosconi

When fasting becomes risky (the “don’t push it” zone)

Fasting gets dangerous faster when it stacks with:

- Dehydration

- Heat exposure

- Hard training

- Poor sleep

- Very low body fat

- Illness

- Diabetes meds or blood pressure meds

- A history of disordered eating

Practical “stop fasting” warning signs

If a reader wants a rule-of-thumb, give them something clear:

- Fainting or near-fainting

- Confusion, severe weakness, or new chest pain

- Persistent vomiting

- Heart palpitations that don’t settle

- Signs of severe dehydration (very dark urine + dizziness + rapid heartbeat)

- “I can’t function” headaches despite water and rest

How to fast more safely (without turning it into a test of willpower)

Start smaller than you think

A lot of people jump straight to 16:8 and then blame themselves when they crash. A gentler ramp works better:

- Week 1: 12:12

- Week 2: 13:11

- Week 3: 14:10

- Then decide if 16:8 even improves your life

Prioritize hydration (and don’t fear salt if appropriate)

Many “fasting side effects” are fluid/electrolyte issues in disguise. Some people do fine with just water; others do better adding electrolytes—especially if they sweat a lot.

Break your fast like an adult, not like a revenge story

A common failure pattern:

- Fast longer than planned → get ravenous → break with a huge heavy meal → feel sick → “fasting doesn’t work”

Instead, use a structured break (I give a full guide in the next article below).

Real-life examples (so readers recognize themselves)

- Office worker fasting for focus: 14:10 with a protein-rich lunch and earlier dinner is often easier than skipping dinner and going to bed hungry.

- Active person training hard: a strict daily fast can backfire; a smaller fasting window + consistent protein may preserve performance.

- Religious fasting: planning the pre-fast meal and break-fast meal is often the difference between “peaceful day” and “headache day.”

FAQ

Is a 24-hour fast the same as starvation?

Not usually. For many healthy adults, a single day without food is uncomfortable but not inherently “starvation.” Context matters (hydration, health status, medications).

Will fasting “burn muscle”?

Short fasts typically shift fuel use toward stored energy. Muscle loss risk increases with prolonged inadequate intake, low protein overall, and no resistance training.

Can fasting be dangerous even if I’m overweight?

Yes. Weight status doesn’t automatically protect someone from dehydration, electrolyte problems, medication issues, or fainting.

Conclusion (recap)

Fasting and starvation share some biology—but they’re not the same experience. Planned, well-hydrated, well-fed intermittent fasting is fundamentally different from prolonged deprivation, in which the body’s systems start to pay the price.