Introduction

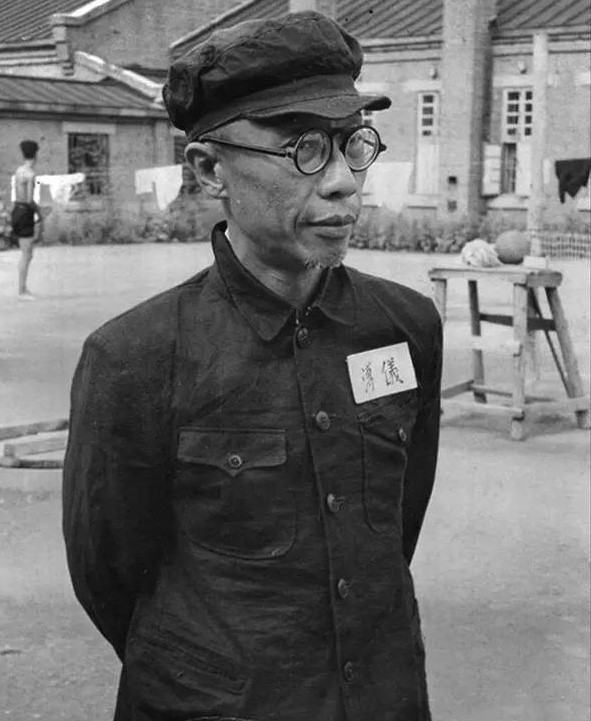

In the grand sweep of Chinese history, few figures are as hauntingly symbolic as Puyi, the last emperor of China. His life, which began in the opulent isolation of the Forbidden City and ended as an ordinary citizen in Communist China, mirrors the dramatic transformation of a nation. Puyi’s story is not just about the end of a dynasty—it’s about the collision of tradition and modernity, the vulnerability of power, and the human cost of political upheaval.

As the historian Edward Behr wrote, “Puyi was a man who lived several lives, each one a reflection of the China he inhabited—imperial, colonial, revolutionary, and modern.” This article explores the rise and fall of China’s last emperor, the forces that shaped his destiny, and the legacy he left behind.

The Qing Dynasty: China’s Last Imperial House

To understand Puyi’s story, we must first look at the world he was born into. The Qing Dynasty, established by the Manchu people in 1644, was the last in a long line of Chinese dynasties. For centuries, the Qing emperors ruled over a vast, diverse empire, presiding from the Forbidden City in Beijing—a palace complex so grand and mysterious that it was said to be the center of the world.

But by the late 19th century, the Qing Dynasty was in crisis. Foreign powers had forced China into humiliating treaties, carved out spheres of influence, and sparked internal rebellions. The Taiping Rebellion, the Opium Wars, and the Boxer Uprising had all weakened the imperial system. Corruption and incompetence at court further eroded the dynasty’s legitimacy.

As the 20th century dawned, the Qing court was desperately clinging to power, even as revolutionary ideas swept through the country. The empire that had once seemed eternal was now teetering on the brink.

The Making of a Child Emperor

Puyi was born in 1906 into the Aisin-Gioro clan, the imperial family of the Qing. His early years were unremarkable—until fate intervened. In 1908, the Guangxu Emperor died without an heir, and the formidable Empress Dowager Cixi, who had ruled China from behind the scenes for decades, was dying. In a final act of political maneuvering, Cixi chose the two-year-old Puyi as the new emperor.

The decision was both practical and symbolic. A child emperor could be easily controlled by regents and court officials, allowing the Manchu elite to maintain their grip on power. But it was also a sign of desperation—a last attempt to preserve a crumbling dynasty.

Puyi later recalled the moment he was taken from his family.

“I remember being carried, crying, through the palace gates. I did not understand that I was being made emperor. I only knew that I was being taken away from my mother.”

— Puyi, From Emperor to Citizen

On December 2, 1908, Puyi was enthroned as the Xuantong Emperor. He was not yet three years old.

Life in the Forbidden City: Splendor and Solitude

The Forbidden City was a world unto itself—a labyrinth of courtyards, halls, and gardens, inhabited by eunuchs, concubines, and officials. For Puyi, it was both a palace and a prison. He was surrounded by luxury, but also by strict rules and constant surveillance.

His daily life was governed by ritual. He wore elaborate robes, performed ancient ceremonies, and was addressed as the “Son of Heaven.” Yet, he was often lonely and frightened. His only companions were his younger brother, a few playmates, and his British tutor, Reginald Johnston, who would later become a key figure in his life.

Johnston described Puyi as “a boy of intelligence and curiosity, but also of deep sadness—a child who bore the weight of an empire’s expectations.”

“He was a prisoner of tradition, a living relic of a vanished world.”

— Reginald Johnston, Twilight in the Forbidden City

The Fall of the Qing: Revolution and Abdication

Outside the palace walls, China was changing rapidly. Revolutionary groups, inspired by Western ideas and angered by imperial misrule, were calling for the end of the monarchy. In 1911, the Xinhai Revolution erupted, led by figures like Sun Yat-sen. The revolutionaries quickly gained support, and the Qing government was powerless to stop them.

By early 1912, the dynasty had collapsed. On February 12, 1912, the six-year-old Puyi was forced to abdicate, ending more than two thousand years of imperial rule in China. The abdication edict, written in Puyi’s name, declared:

“We, the Emperor, have resolved to abdicate in favor of a republican government, in order to unite the people and preserve peace.”

Remarkably, the new Republic of China allowed Puyi to remain in the Forbidden City as a “retired emperor,” with a small court and a generous stipend. But his world was shrinking. The palace, once the heart of an empire, became a gilded cage.

The Puppet Emperor: Manchukuo and Japanese Ambitions

Puyi’s life took a dramatic turn in the 1930s. After being expelled from the Forbidden City in 1924, he lived in exile in Tianjin, where he was courted by Japanese agents. In 1932, the Japanese, who had invaded Manchuria, installed Puyi as the puppet ruler of their new state, Manchukuo.

As “Emperor” of Manchukuo, Puyi was little more than a figurehead. The real power lay with the Japanese military.

The experience left him bitter and disillusioned. When Japan was defeated in 1945, Puyi was captured by Soviet forces and sent to a prison camp in Siberia.

“I was a puppet, manipulated by others. I wore the robes of an emperor, but I had no authority, no freedom.” – Puyi

Re-education and Redemption: Puyi in Communist China

In 1950, Puyi was handed over to the new Communist government in China. He spent nearly a decade in a re-education camp, where he was forced to confront his past and renounce his imperial identity. The process was harsh, but Puyi eventually embraced his new life.

In 1959, he was released and allowed to live as an ordinary citizen in Beijing. He worked as a gardener, a researcher, and later as a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. Puyi’s transformation from emperor to commoner was complete.

He reflected on his journey in his memoirs:

“I have learned that the past is gone, and that I must live as a man among men, not as a god among mortals.”

Legacy: The End of an Era and the Birth of Modern China

Puyi’s life is a microcosm of China’s tumultuous 20th century. He witnessed the fall of the imperial system, the rise of republicanism, the horrors of war and occupation, and the birth of a new, revolutionary China. His story is a reminder of how quickly history can change—and how individuals are often swept along by forces beyond their control.

As historian Jonathan Spence observed:

“Puyi was both a victim and a symbol—a man who embodied the end of one world and the uncertain beginning of another.”

Puyi’s Life and China’s Transformation

| Year | Puyi’s Life Event | China’s Historical Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1906 | Born in Beijing | Qing Dynasty in decline |

| 1908 | Becomes emperor at age 2 | Death of Guangxu Emperor and Cixi |

| 1911 | Xinhai Revolution | End of imperial rule |

| 1912 | Forced to abdicate at age 6 | Republic of China established |

| 1924 | Expelled from Forbidden City | Warlord era, political chaos |

| 1932 | Installed as emperor of Manchukuo | Japanese occupation of Manchuria |

| 1945 | Captured by Soviets | End of World War II |

| 1950 | Returned to China, imprisoned | Communist victory, People’s Republic |

| 1959 | Released, becomes ordinary citizen | Maoist China, social transformation |

| 1967 | Dies in Beijing | Cultural Revolution |

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Puyi become emperor as a child?

Puyi was chosen by Empress Dowager Cixi in 1908 because he was a direct descendant of the imperial family and, as a toddler, could be easily controlled by regents. The court hoped this would stabilize the dynasty, but it was too late.

What was life like for Puyi after abdication?

Initially, Puyi lived in the Forbidden City as a “retired emperor,” but he was eventually expelled and lived in exile. Later, he became a puppet ruler for the Japanese and, after World War II, was re-educated and lived as a common citizen in Communist China.

What does Puyi’s story tell us about China’s history?

Puyi’s life reflects the dramatic changes in China during the 20th century—from imperial rule to republic, from foreign occupation to revolution. His personal journey is a symbol of the nation’s transformation.

Conclusion: The Last Emperor’s Enduring Lesson

Puyi’s life is a testament to the impermanence of power and the resilience of the human spirit. From the Dragon Throne to a humble garden, he experienced the heights of privilege and the depths of obscurity. His story reminds us that history is not just about great events, but about the people who live through them.

As Puyi himself wrote, “I watched an empire die, and in its place, a new China was born.” His legacy endures as a bridge between the old and the new, a living witness to the end of an era and the birth of modern China.