Sugar is woven into our modern diet, from fruit and milk to pastries and sodas. Yet “sugar” isn’t a single thing—its source, structure, and the foods it comes with all shape how it affects your brain and body. Below is a clear, research-based guide that answers key questions about sugar’s impact on the brain, the difference between natural and added sugars, what happens when you cut sugar, healthy alternatives, and how to track a safe daily intake.

How sugar affects the brain

- Rapid energy and dopamine release: Glucose is the brain’s primary fuel. When you consume sugar—especially rapidly absorbed forms like sugary drinks—blood glucose rises quickly. This triggers insulin release and a surge of dopamine in the brain’s reward pathways (notably the nucleus accumbens). The result is brief heightened alertness, pleasure, and motivation.

- Habit and preference formation: Frequent spikes in dopamine from highly palatable, high-sugar foods can reinforce habits and cravings. Over time, some people experience reduced reward sensitivity, prompting them to seek larger or more frequent “hits” for the same satisfaction.

- Mood and cognitive swings: Fast increases in blood sugar can be followed by dips (“reactive hypoglycemia”) 1–3 hours later, leading to fatigue, irritability, and difficulty concentrating. Large fluctuations, rather than steady levels, are what often undermine focus and mood.

- Inflammation and long-term risk: Chronically high intake of added sugar is associated with systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and higher risks of cardiometabolic disease. Emerging evidence links these processes to diminished cognitive function over time and a higher risk of conditions like vascular dementia. Stable glucose is protective; volatility is not.

Natural sugars in fruit vs. industrial/added sugars: Are they the same?

Chemically, glucose and fructose molecules are the same regardless of source. The difference lies in the delivery package and dose.

- Fruit: Whole fruits contain sugars along with fiber, water, vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols. Fiber slows absorption, flattening glucose spikes. Chewing and volume promote satiety, making overconsumption less likely. Fruit intake is consistently associated with better cardiometabolic outcomes.

- Added sugars: Table sugar (sucrose), high-fructose corn syrup, syrups, and sugars added during processing lack fiber and often appear in ultra-processed foods that are energy-dense and easy to overeat. These produce faster glucose excursions, stronger reward responses, and less satiety.

- Fructose context matters: Fructose in fruit is typically modest and buffered by fiber and nutrients. High-dose free fructose (e.g., in sweetened beverages) bypasses some regulatory steps, burdens the liver, and can drive triglyceride production when consumed in excess.

Bottom line: The brain’s immediate response to sugar molecules may be similar, but the metabolic and behavioral effects of sugar in whole fruit differ markedly from those of added sugars in processed foods and drinks.

What happens to the brain when you stop eating added sugar?

- Short-term (days to 2 weeks): Many people report reduced cravings after 5–14 days. Early on, you may feel headaches, irritability, or low energy as dopamine and glucose volatility stabilize—similar to breaking a habit loop rather than a true “detox.”

- Medium-term (2–8 weeks): Fewer energy crashes, improved mood stability, better sleep quality for some, and enhanced taste sensitivity (naturally sweet foods taste sweeter).

- Long-term: More stable insulin signaling, fewer glucose swings, and potential improvements in attention and executive function related to steadier energy availability. If weight and metabolic markers improve, downstream brain health benefits likely accrue.

Note: Cutting all sugar is neither necessary nor always helpful. Most benefits come from reducing added sugars and ultra-processed foods, not from avoiding whole fruit or dairy.

Healthier alternatives to added sugar

- Whole-food sweetness:

- Whole fruits (fresh, frozen, or unsweetened dried in moderation)

- Roasted vegetables with natural sweetness (carrots, sweet potatoes, squash, beets)

- Spices and extracts (cinnamon, vanilla, cardamom, citrus zest, cocoa)

- Minimal-added-sugar strategies:

- Use small amounts of honey or maple syrup primarily for flavor, not bulk sweetness. They are still sugars; the advantage is taste potency and trace compounds, not fundamentally different metabolism.

- Date paste or mashed ripe banana in baking—for fiber and nutrients with sweetness.

- Non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS):

- Options include stevia, monk fruit (luo han guo), allulose, erythritol, sucralose, and acesulfame-K.

- Pros: Reduce added sugar and calories; can help transition away from high-sugar products.

- Cons and caveats: Some people experience GI discomfort (especially with sugar alcohols); taste profiles vary; they may preserve a preference for very sweet flavors. Evidence on long-term metabolic and gut microbiome effects is mixed and evolving. For most healthy adults, moderate use is reasonable.

- Behavioral swaps:

- Coffee/tea: Gradually step down sweetening over 2–4 weeks.

- Breakfast: Choose high-fiber, protein-rich options (e.g., Greek yogurt with berries and nuts; eggs with vegetables; oats with chia and cinnamon) to reduce mid-morning crashes.

How much sugar per day—and what happens to the excess?

- Recommended limits (added sugar, not total sugar from whole foods):

- World Health Organization: Less than 10% of total daily calories from added sugars; a further reduction below 5% (~25 g/day for most adults) provides additional benefits.

- American Heart Association: ≤36 g/day for most men; ≤25 g/day for most women; less for children.

- Tracking practicalities:

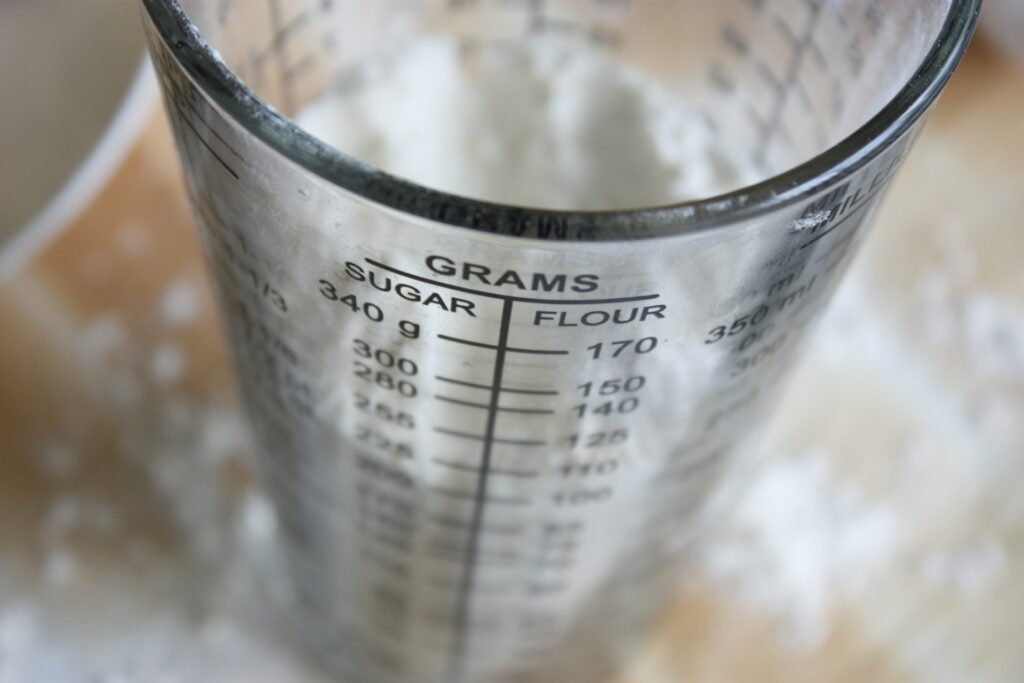

- Read labels for “Added Sugars” (in grams). 4 grams ≈ 1 teaspoon.

- Watch beverages: Sugary drinks are the top source of excess added sugar.

- Use a simple daily “budget” (e.g., 25–36 g) and plan where you want to spend it (a sweetened yogurt or a small dessert).

- Prefer whole fruits over juices. A glass of juice can contain the sugar of multiple fruits without the fiber.

- What the body does with excess sugar:

- Immediate use: Cells take up glucose for energy under insulin’s direction.

- Short-term storage: Excess glucose is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles.

- Conversion to fat (de novo lipogenesis): When glycogen stores are replete, the liver converts excess—especially high fructose loads—into fatty acids, contributing to elevated triglycerides and liver fat.

- Long-term effects: Chronic surplus contributes to weight gain, insulin resistance, fatty liver, and vascular changes that threaten brain and heart health.

A simple plan to stabilize brain energy and reduce added sugar

- Anchor each meal with protein, fiber, and healthy fats to blunt glucose spikes.

- Front-load whole foods: vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and whole fruits.

- Make beverages count: Choose water, sparkling water, unsweetened tea/coffee; keep sugary drinks for rare occasions.

- If using sweeteners, use less over time; retrain your palate gradually.

- Sleep and stress matter: Poor sleep and high stress increase sweet cravings; addressing these reduces reliance on sugar for quick energy.

Key takeaways:

- The brain thrives on steady glucose, not big spikes and crashes.

- Whole fruits are not metabolically equivalent to added sugars because of fiber and nutrients.

- Cutting added sugar leads to fewer cravings and steadier mood and focus after an initial adjustment.

- Healthy alternatives include whole-food sweetness, spices, and moderate use of non-nutritive sweeteners.

- Track added sugars using label “Added Sugars,” keeping most adults near 25–36 g/day, and remember that excess sugar will be stored—first as glycogen, then as fat—if intake routinely exceeds needs.