Many people believe they need thousands of dollars to begin investing, but that’s simply not true. With just $100, you can start building wealth and learning valuable investment skills. The key is starting now rather than waiting for the “perfect” amount.

“The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.” – Chinese Proverb

Understanding the Basics: What Is Investing?

Investing means putting your money into assets that have the potential to grow in value over time. Unlike saving, where your money sits in a bank account earning minimal interest, investing allows your money to work for you through compound growth.

Key Investment Principles for Beginners

Start Early: Time is your greatest asset when investing. Even small amounts can grow significantly over decades through compound interest.

Diversification: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Spread your investments across different types of assets to reduce risk.

Stay Consistent: Regular investing, even small amounts, often outperforms trying to time the market with larger sums.

Best Investment Options for $100

1. Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

ETFs are perfect for beginners because they offer instant diversification. With $100, you can buy shares in funds that track entire market indexes like the S&P 500.

Popular beginner ETFs:

- SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY)

- Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI)

- iShares Core MSCI Total International Stock ETF (IXUS)

2. Fractional Shares

Many brokers now offer fractional shares, allowing you to buy portions of expensive stocks. This means you can own a piece of companies like Apple or Amazon with just $100.

3. Target-Date Funds

These funds automatically adjust their investment mix based on your retirement timeline, making them ideal for hands-off investors.

4. Robo-Advisors

Platforms like Betterment and Wealthfront create diversified portfolios for you, often with low minimum investments and fees.

Step-by-Step Guide to Investing Your First $100

Step 1: Choose a Brokerage Account

Select a reputable broker with:

- No account minimums

- Commission-free stock and ETF trades

- User-friendly mobile app

- Educational resources

Popular options: Fidelity, Charles Schwab, E*TRADE, Robinhood

Step 2: Determine Your Risk Tolerance

Consider your age, financial goals, and comfort level with market fluctuations. Generally:

- Conservative: 70% bonds, 30% stocks

- Moderate: 50% bonds, 50% stocks

- Aggressive: 20% bonds, 80% stocks

Step 3: Make Your First Investment

For beginners, consider starting with a broad market ETF that tracks the S&P 500. This gives you exposure to 500 of America’s largest companies.

Step 4: Set Up Automatic Investing

Many brokers allow you to set up automatic investments. Even adding $25 monthly can significantly impact your long-term wealth.

Common Beginner Mistakes to Avoid

Trying to Time the Market: Nobody can consistently predict market movements. Focus on time in the market, not timing the market.

Emotional Investing: Don’t panic sell during market downturns or chase hot stocks during bull markets.

Ignoring Fees: High fees can erode returns over time. Look for low-cost index funds and ETFs.

Lack of Diversification: Don’t invest everything in one stock or sector.

Building Your Investment Strategy

Dollar-Cost Averaging

This strategy involves investing a fixed amount regularly, regardless of market conditions. It helps reduce the impact of market volatility and removes emotion from investing decisions.

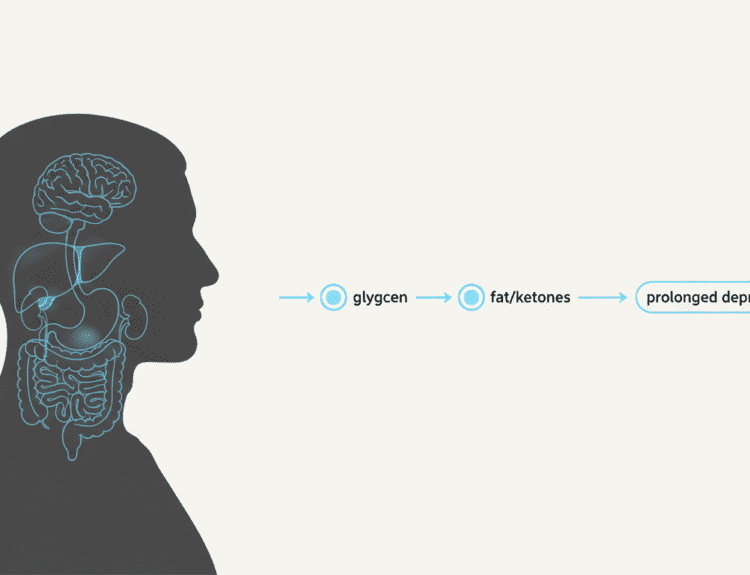

The Power of Compound Growth

With a 7% annual return (historical stock market average), your $100 could grow to:

-$200 in 10 years

-$400 in 20 years

-$800 in 30 years

Add just $50 monthly, and these numbers become much more impressive.

Tax-Advantaged Accounts to Consider

Roth IRA

Contributions are made with after-tax dollars, but withdrawals in retirement are tax-free. Perfect for young investors in lower tax brackets.

Traditional IRA

Contributions may be tax-deductible, which can reduce your current tax bill. Withdrawals in retirement are taxed as ordinary income.

401(k)

If your employer offers matching contributions, prioritize this over other investments—it’s free money.

Monitoring and Adjusting Your Portfolio

Review your investments quarterly, not daily. Market volatility is normal, and frequent checking can lead to emotional decisions. Focus on:

- Rebalancing annually

- Increasing contributions when possible

- Staying committed to your long-term strategy

“An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.” – Benjamin Franklin

Resources for Continued Learning

Books:

- “The Bogleheads’ Guide to Investing” by Taylor Larimore

- “A Random Walk Down Wall Street” by Burton Malkiel

- “The Simple Path to Wealth” by JL Collins

Websites:

- SEC Investor.gov – Official SEC investor education

- Morningstar – Investment research and analysis

- Bogleheads.org – Community-driven investment advice

Taking Action Today

The most important step is starting. Don’t wait for the perfect moment or more money. Open a brokerage account, invest your first $100 in a broad market ETF, and begin your wealth-building journey.

Remember, every successful investor started with their first dollar. Your $100 today could be the foundation of significant wealth tomorrow.