Panic attacks are sudden, intense surges of fear or discomfort that peak within minutes and trigger strong physical and psychological symptoms—even when there is no real danger. They can feel overwhelming, but they are treatable, and many people recover fully with the right strategies and support.

This article explains what panic attacks are, how they feel, why they happen, how to manage them in the moment, and how to reduce or prevent them over time. It also covers when to seek help and how to support someone going through one.

What is a panic attack?

A panic attack is an abrupt episode of intense fear that activates the body’s “fight‑or‑flight” response. Symptoms often come on quickly and peak within 10 minutes, though some people may feel after-effects for longer. Panic attacks can occur unexpectedly or in response to a trigger. When attacks are recurrent and unpredictable with ongoing worry about having more, it may be diagnosed as panic disorder.

Common symptoms

Panic attack symptoms vary, but often include:

- Racing or pounding heart (palpitations)

- Shortness of breath, chest tightness, or a choking sensation

- Sweating, trembling, or shaking

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, or faintness

- Nausea or abdominal cramping

- Numbness or tingling (often in hands/feet)

- Chills or hot flashes

- Feelings of unreality (derealization) or detachment from self (depersonalization)

- Intense fears such as “I’m losing control,” “I’m having a heart attack,” or “I’m going to die”

These symptoms are uncomfortable but not dangerous. However, because they can resemble serious medical issues, it’s reasonable to seek medical evaluation—especially the first time or if symptoms change significantly. Sources: Mayo Clinic, Northwestern Medicine.

What a panic attack feels like (inside the body)

Panic attacks are an exaggerated stress response:

- The brain detects threat (real or perceived) and signals the autonomic nervous system.

- Adrenaline surges, heart rate and breathing increase, blood flow shifts to large muscles, and digestion slows.

- These changes can cause chest tightness, shortness of breath, dizziness, tingling, and nausea—the very sensations that can intensify fear, creating a feedback loop.

Recognizing this physiology helps break the cycle: the body is doing what it’s designed to do under stress, even if the alarm is a false one. See: Mind.

Triggers and risk factors

Panic attacks can be:

- Unexpected (out of the blue), or

- Situationally bound (e.g., driving, crowds, confined spaces), or

- Situationally predisposed (more likely in certain contexts but not guaranteed)

Contributing factors may include:

- Genetics and family history

- Major life stress or transitions (loss, illness, conflict)

- Temperament sensitive to stress or negative affect

- Medical issues (thyroid dysfunction, stimulant use), or substances (caffeine, nicotine, cannabis)

- Learned associations (e.g., having an attack in a specific place)

References: Mayo Clinic.

Panic attacks vs. “anxiety attacks”

- Panic attacks: Sudden onset, intense physical symptoms, peak within minutes; may occur without an obvious trigger.

- Anxiety “attacks”: Not a formal DSM-5 diagnosis; usually a gradual build-up of worry and tension tied to stressors, can last longer with more cognitive symptoms (rumination, restlessness). A brief primer: Mind.

What to do during a panic attack: immediate strategies

These techniques can reduce intensity and help the wave pass sooner. Practice them when calm so they’re easier to use under stress.

- Reassure yourself

- Label it: “This is a panic attack. It’s uncomfortable, not dangerous. It will pass.”

- Slow the breath

- Try a 4‑1‑6 pattern: inhale through the nose for 4, pause 1, exhale through the mouth for 6. Aim for ~6 breaths per minute.

- Keep shoulders relaxed and breathe into your belly. Long, slow exhales signal safety to the nervous system.

- Grounding with the senses

- The 5‑4‑3‑2‑1 method: name 5 things you see, 4 you feel/touch, 3 you hear, 2 you smell, 1 you taste. This shifts attention from internal sensations to the present environment.

- Temperature shift

- Briefly place a cool pack or wrapped ice on wrists/face, or splash cool water. This can dampen the adrenaline response.

- Progressive muscle release

- Tense one muscle group for ~5 seconds, release for ~10; move from feet to face to discharge physical tension.

- Posture and space

- Uncross legs, plant feet, loosen tight clothing, get fresh air if possible.

- Gentle movement

- Slow walking or stamping lightly can regulate breathing and metabolize adrenaline.

For supportive summaries of these methods, see Mind.

Longer-term control: prevention and reduction

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- First-line treatment for panic disorder. Helps reframe catastrophic thoughts, reduce fear of bodily sensations, and end avoidance patterns.

- Interoceptive exposure (a CBT tool) safely recreates panic-like sensations (e.g., spinning to feel dizzy) to teach the brain they’re tolerable and not dangerous.

- Exposure therapy

- Gradually face avoided situations (e.g., elevators, highways) in a planned, stepwise way, often combined with breathing/grounding skills.

- Medications

- SSRIs or SNRIs can reduce frequency and severity of attacks; benefits build over weeks.

- Benzodiazepines may be used short term or situationally; discuss risks (dependence, sedation) with your clinician.

- Treatment plans are individualized; combine with therapy for best outcomes. See overview in Mayo Clinic.

- Lifestyle supports

- Sleep: consistent schedule and wind-down routine.

- Exercise: regular aerobic activity reduces baseline anxiety.

- Substances: reduce caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol; consider timing and total intake.

- Nutrition and hydration: steady energy and blood sugar can reduce vulnerability to symptoms that mimic anxiety (e.g., jitters).

- Skill maintenance

- Daily practice of slow breathing and grounding when calm.

- Keep a brief “coping card” on your phone with your top 2–3 steps.

- Tracking and triggers

- Use a simple log: time, situation, sensations, thoughts, what helped. Patterns guide treatment and empower you to plan.

When to seek medical care

- First-time or severe symptoms (especially chest pain or shortness of breath) to rule out medical issues.

- Recurrent, unexpected attacks or persistent worry about more attacks (possible panic disorder).

- Significant life impact: avoidance of work, social activity, travel, or daily routines.

- Co-occurring concerns: depression, substance use, or suicidal thoughts. If you’re in immediate danger, seek emergency help.

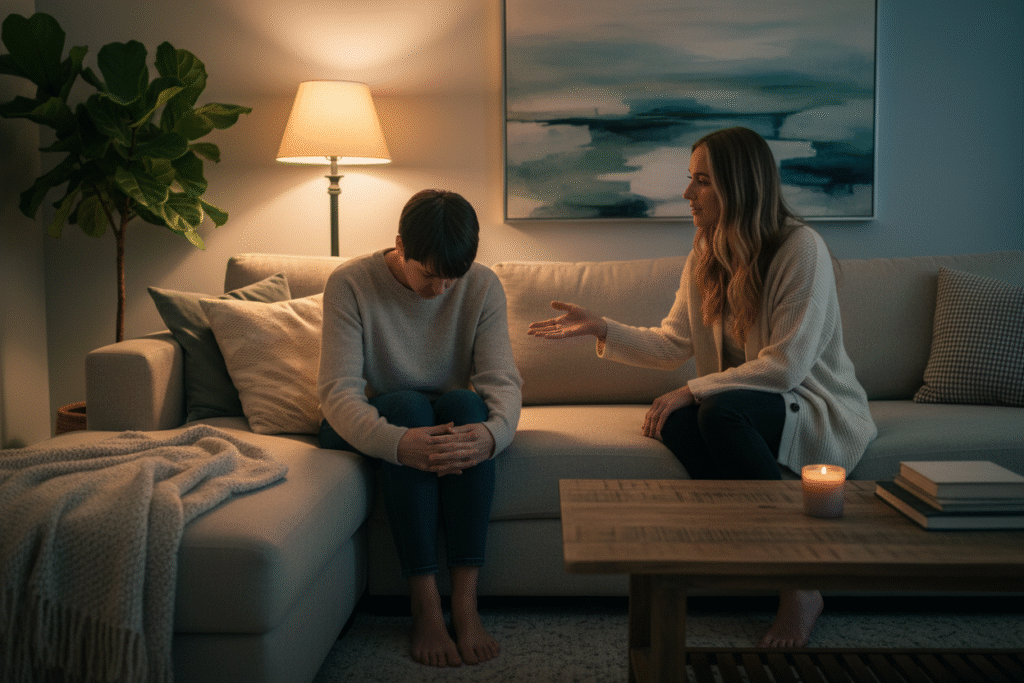

How to support someone having a panic attack

- Stay calm; use a gentle, steady voice.

- Validate: “You’re safe. I’m here. This will pass.”

- Guide slow breathing or grounding steps.

- Offer a quiet space and reduce stimulation; don’t argue with their fear or force them to “snap out of it.”

- Ask what helps them; respect preferences.

Prognosis and recovery

With appropriate treatment—especially CBT, with or without medication—most people experience major improvement. The goal is not to eliminate all anxiety (a normal human signal), but to:

- Reduce the frequency and intensity of attacks

- Restore confidence and daily functioning

- Break the fear-of-fear cycle

Relapses can happen under stress; skills you’ve practiced remain effective and help you regain control quickly.

A two-step micro-plan you can save

- Step 1: Breathe 4‑1‑6 for 60–90 seconds; relax shoulders and belly.

- Step 2: Name 5 things you see, 4 you feel, 3 you hear, 2 you smell, 1 you taste. Then tell yourself: “Uncomfortable, not dangerous. It will pass.”

Conclusion

Panic attacks are intense but temporary surges of fear driven by the body’s natural alarm system. While they can feel alarming and disruptive, they are treatable. With evidence-based tools like breathing and grounding techniques, cognitive behavioral therapy (including interoceptive and situational exposure), and, when appropriate, medication, most people significantly reduce both the intensity and frequency of attacks and regain confidence in daily life. The key is to break the fear-of-fear cycle, practice skills when calm, and seek professional support if attacks recur or limit your activities. Recovery is not about never feeling anxious again—it’s about rebuilding trust in your body and your ability to navigate anxious moments with clarity and control.